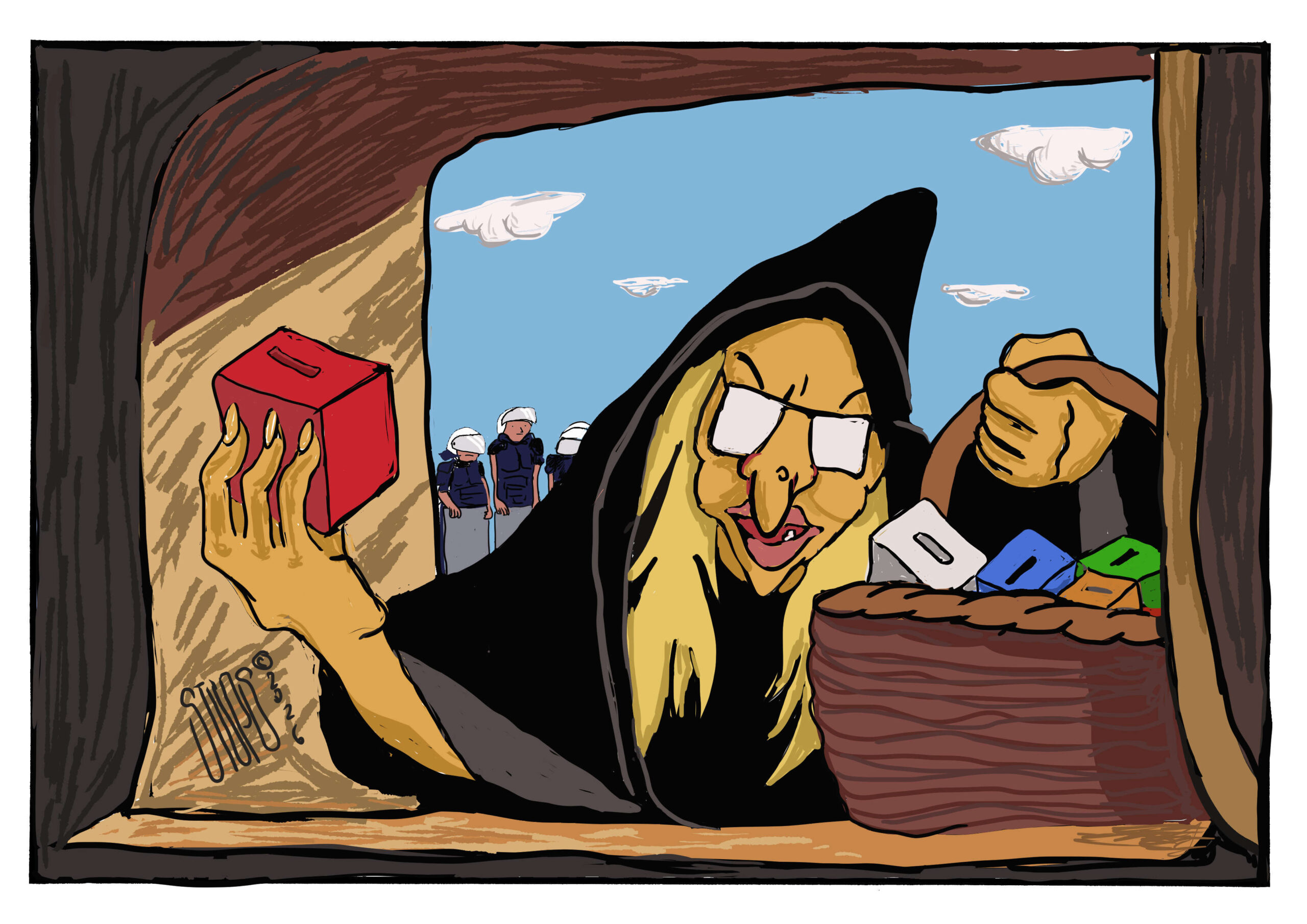

No wagers were being laid on election results for the Vojvodina Assembly. If they were, the highest profit would make betting that Nenad Čanak’s League of Social-Democrats in Vojvodina would won the equal number of representatives as the coalition Vojislav Koštunica – Velimir Ilić. This is actually the greatest surprise. Many however were surprised by an absolute victory of the coalition For a European Vojvodina led by Boris Tadić and Mladjan Dinkić. The third surprise was a low number of voters and, within them, the highest number of those of Europe-orientated. This is contrary to hitherto claims that the Serbian Radical Party has the most disciplined membership and the most obedient electorate army. The Radicals had in the second round 39 candidates, they were promised the support of those who in the first round had voted for the coalition Populists – Socialists, but have won only four of 60 mandates. What else, but fiasco!

No wagers were being laid on election results for the Vojvodina Assembly. If they were, the highest profit would make betting that Nenad Čanak’s League of Social-Democrats in Vojvodina would won the equal number of representatives as the coalition Vojislav Koštunica – Velimir Ilić. This is actually the greatest surprise. Many however were surprised by an absolute victory of the coalition For a European Vojvodina led by Boris Tadić and Mladjan Dinkić. The third surprise was a low number of voters and, within them, the highest number of those of Europe-orientated. This is contrary to hitherto claims that the Serbian Radical Party has the most disciplined membership and the most obedient electorate army. The Radicals had in the second round 39 candidates, they were promised the support of those who in the first round had voted for the coalition Populists – Socialists, but have won only four of 60 mandates. What else, but fiasco!

Šid, Sremska Mitrovica, Pećinci, Ruma, Stara Pazova and Indjija have thus busted claims about a radical Vojvodina. The European block has won also in Bačka Palanka and Vrbas which were believed to be the Radicals’ strongholds.

Elections in Vojvodina have confirmed that the Radicals are strong only as a party. Individually, when citizens choose between two candidates, with names and surnames, the chances of Šešelj’s frontmen plunge. The reason is their thin basis of human resources, actually the fact that they have no person of high standing in any milieu. Many voters who at the parliamentary elections voted for the Radicals didn’t vote in the second round of elections because they didn’t want to vote for candidates from their party they would later be ashamed of.

At the elections held September 2000, the coalition DOS won the absolute majority in Vojvodina – 118 of 120 representatives. In the following four years almost nothing from those ardent pre-elections promises was being realized. And how only generous they sounded – from Vojvodina’s money in Vojvodina’s pocket to an executive, legal and legislative autonomy. Everything finally ended in the so-called “omnibus” law with which the Provincial executive government neither knows what to do nor how to implement it. Until 2004, the ruling coalition was mostly engaged on satisfying parties’ appetites. Vojvodina hadn’t become a locomotive pulling Serbia onward to Europe. That year, after elections, a sort of mixed majority (narrow) was being formed in which Bogoljub Karić’s Movement for Serbia tipped the scale. Then also the government was formed on the feudal principle, which works also on national level: each party had its ministries in which other partners had no right to peep let alone to intervene. Promises that knowledge and professionalism would be above politics and party’s membership was forgotten already in the first period of the Democrats in office. Today, nobody even mentions it on the eve of elections, because power of the party’s membership card is notorious.

None of the official Vojvodina’s institutions didn’t participate in passing a new Serbian Constitution (neither did others, because there was no any public discussion about it). Therefore the Province has got in the “mother of all laws” exactly as much power as it was possible on the basis of then power balance in Belgrade. If someone from the Provincial government had made any attempts to amend this, it was on level of internal communication in the Democratic Party. Belgrade allegedly said to the president of the Executive Council of the AP Vojvodina Assembly, Bojan Pajtić, to avoid stirring up because at the moment national interests were in the first place.

Winners have announced that they will form – though they can freely rule on their own – an additional majority with the Hungarian coalition and the League of Social-Democrats in Vojvodina. There is no indication whether this majority will accept the current status of Vojvodina in Serbia as something final or will try to agree about platform to demand a wider autonomy. The first is more likely as it seems that the slogan “Vojvodina to Vojvodina’s people” after eight years of democratic government has lost its sense. Those who once launched it enjoy no more the confidence of voters and the winning coalition believes that the issue of autonomy will vanish by itself from the agenda once when Serbia joins Europe. Even if Novi Sad submits the list of its demands from the summer of 2000 or possibly a revised one, it will be at least frowning on even by the most democratic Belgrade circles. Therefore, the supreme legal act of the Autonomous Province will remain to be its Status (Article 185) stipulating that the “Republic of Serbia may pass certain of its functions over to jurisdiction the Autonomous Provinces and the units of local self-government” (Article 178) and that the “budget of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina should amount to at least 7.0 percent of the budget of the Republic of Serbia, provided that 3.0 of 7.0 percent should be used for investing in capital expenditure” (Article 184).

Winners, as it is appropriate, have gentlemanly offered a hand to the Hungarian coalition and the League of Social-Democrats in Vojvodina. Should the Socialists enter the government at the state level, there is no doubt that they would get a piece of cake in Vojvodina. Should, on the other hand, the government in Belgrade constitute Šešelj, Koštunica and Dačić, democratic and European Vojvodina should come into position to plead, on knees, for each of those seven percent in relation to the budget of Serbia.

All in all, what does the victory of the coalition For a European Vojvodina mean? In the moral sense – plenty! Politically – only in the measure in which is Vojvodina political factor in Serbia.

(www.magazinvojvodina.com)

STUPS: Ponuda

STUPS: Ponuda